Christopher Marzullo is Senior Manager - Fixed Income Middle Office of Lord Abbett, LLC, which he joined in April 2002, initially as supervisor. Prior to joining Lord Abbett, LLC, Christopher was at Nomura Securities International, from April 1996 to April 2002. He began in that organisation in clearance settling trades on the Fedwire system and with the Depository Trust Company (DTC), also backing up MBS allocations and MBSCC groups, and then moved to several desks including repo, government/agency, and pass-throughs/CMOs. Prior to joining Nomura Securities, Christopher had been at Donaldson, Lufkin and Jenrette, from January 1994 to April 1996, beginning his career in MBS allocations and clearance. He is a graduate of Bernard Baruch College, City University of New York, and also has a Series 7 licence. Christopher is a member of committees in the Asset Managers Forum (AMF) that work towards alleviating fails and overdraft instances.

Peter Kelly was a director in fixed income operations with Nomura Securities when this paper was written. He was with Nomura from November 1995. His responsibilities included managing the residential and commercial mortgage groups, which included principal and interest (P&I) processing, accrual reconciliation and trade support. Throughout his tenure at Nomura, Peter managed mortgage-backed security (MBS) allocations, MBS Clearing Corporation (MBSCC) processing, collateralised mortgage obligation (CMO) operations, all of the fixed income clearance groups and the security master functions. Peter started his career in 1988 with JPMorgan in corporate finance operations. He managed the processing for the special loan portfolio, as well as for the money transfer investigations unit. In 1991, he transferred to JPMorgan Securities and became supervisor for the MBS allocations group, in which role he continued until he left the firm in 1995. Peter has a degree in economics from St Francis College and a Master of Business Administration degree in finance from Pace University. He is currently pursuing other consulting opportunities.

Frederick Lipinski is a director in fixed income operations at Nomura Securities. He started in the company in fixed income settlements and was transferred to fixed income trade entry; his responsibilities include MBS, CMO derivatives, government, repo, corporate and whole loan trade support and settlements, as well as whole loan P&I collections. He has been with Nomura since January 1989. Prior to Nomura, Frederick worked at Salomon Brothers in equity fail control, before being transferred to fixed income settlements and repo trade support. He is chairman of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) Government Operations Committee and a member of the Corporate Operations Committee. Frederick has a degree in marketing from Middlesex College.

ABSTRACT

The following paper is written by representatives from the buy and sell sides of the US fixed income securities industry. Its focus is on fail issues that are pertinent to the US markets. The authors are members of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), an industry group that focuses on the needs and problems of the US fixed income markets. In the course of this paper, the authors will show the reasons why fails occur, as well as some of the reactive and preventative actions that may be taken to minimise the number of fails. The paper will also touch on some of the initiatives that have commenced within the industry towards managing fail risk and minimising the number of fails, as well as the number of actual trades that get settled during the course of an average business day. By providing a point of view from both sides of the market, the paper aims to offer a fuller understanding of the practices and procedures in addressing fail issues that vary on each side of the business. The reader will also take away knowledge of the industry's ongoing projects to reduce further the number of fails and the associated risk.

Keywords: fails, Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC), asset manager, broker, round robin, netting

INTRODUCTION

To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin: In this world, nothing is certain but death and taxes.' Had Franklin worked in the securities industry, he might have added fails' to his list of certainties.

Recognising the inevitability of fails and the impossibility of their elimination, the industry has focused instead on minimising them. At the end of each day, most institutional market participants will have fails on their books. These failing items will be confirmed with the parties involved and settled within a day or two. There have, however, been situations in which chronic fails have plagued the industry: the days following 11th September, 2001, for example, and the summer of 2003.

The attack on the World Trade Center and damage to the downtown area of New York created a situation in which trading records were destroyed, and communications were knocked out between the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC)1 and its participant population, as well as clearing banks and their customers. The combination of destroyed records and connectivity problems contributed to the FICC having almost US$440bn worth of government security fails on 12th September, 2001. The numbers gradually decreased as the industry started getting back on line and, by the end of that week, the figure had fallen to around US$90bn - but it took many weeks for affected firms to reconcile their fail issues. The US Treasury actually expanded an existing note issue from US$12bn to US$18bn to help to facilitate deliveries.

In early July 2003, the US Treasury, May 2013, ten-year note experienced excessive borrowing demand, which drove the repo rate for specials to almost zero. This situation spread into settlement fails, which caused buyers of the issue to become lenders, rather than simply holders, of the securities. A concerted effort by the Bond Market Association (BMA), the FICC and their members to identify round robins, re-net failing trades and other initiatives helped, eventually, to eliminate what had become a serious fail issue.

Fails cause enough angst for risk managers - but, while the industry worked feverishly to get things back to normal, these two particular episodes caused risk managers to double up on the antacids. The industry is always trying to find new ways to mitigate fail risk, and these examples show how quickly a systemic failure can spiral out of control and the effort that is required to get things right.

The two major players in the US markets are the broker-dealer side - known as the sell side' - and the asset manager community (hedge funds, pension funds, insurance companies, etc) - known as the buy side'. The goal of this paper is to illustrate the issues associated with fails and how these two sides of the industry attempt to minimise those issues.

A fail occurs when a security transaction does not clear on the settlement or contract date. When a trade is executed, the information is disseminated to the counterparty or any interested party that the client has assigned - that is, a custodian bank. This flow of information is critical to assure proper settlement. The inability to settle a trade carries consequences and creates problems throughout the firms involved. There are various safeguards in place to help to mitigate these issues and to eliminate them quickly so that they do not become major problems.

When a trade fails to settle, the firms involved do not receive cash that could have been invested in revenue-generating transactions; instead, a firm will have to borrow that cash to finance those activities. It is interesting to note that the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) pass-through market - also known as the to be announced' (TBA) market2 - is unique in that it allows participants the chance to fail twice: once during the pool information phase of the transaction and once during the actual settlement phase. The consequence of the fail is that the purchase of the pools is financed for a day or two before the transactional proceeds from the respective delivery are received.

There are many risks and issues that come with a failing transaction that can have serious repercussions if not carefully monitored. Some of the risks involved to a firm when trades fail to settle in a timely fashion are as follows.

Counterparty credit risk

Counterparty credit risk occurs when the failing seller goes out of business before the trade settles, resulting in a loss to the buyer. This requires the buyer to go out and purchase that position, resulting in a huge loss if there has been a substantial market movement from the original trade price. This risk also involves the cost of litigation, due to bankruptcy of the firm failing to receive so that it may recoup any losses.

Ancillary costs to broker-dealers

For broker-dealers, there is a cost associated with following the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules that require firms to set aside capital to cover the cost of a failing trade. Any firm deliveries that fail for more than four business days are subject to capital requirements. Fails of more than 30 calendar days also require capital to be set aside that might have been used instead to finance trading activity.

Customer relationship issues

Fails have the potential to create customer relationship issues: customers tend to get concerned when they do not receive their bonds on the contractual settlement date; some entities, such as foreign central banks, will require a guarantee of delivery. Failure to deliver a bond might result in the customer refusing to do further business with the offending firm.

THE TRADE CONFIRMATION PROCESS

Almost all firms follow procedures to ensure that, when a trade is made, each side has the correct information to effect proper settlement: one side gets the money; the other side gets the securities.

In theory, the trade process is easy - but, in practice, there can be problems. Trade confirmation, for example, can be handled in several ways. In order to process a trade confirmation, a firm must obtain the client's account information, which includes standard settlement instructions (SSIs). A client may have many custodians for transaction processing or only one, which choice is usually dictated by the product and the way in which it settles. The most common way in which to confirm a trade is a mailed document featuring all trade details:

- trade date

- settlement date;

- price

- Committee on Uniform Security Identification Procedures (CUSIP) and security details;

- in what capacity the counterparty is acting (principal or agent).

Once the correct information is determined, the necessary amendments are made to address these exceptions and the trades are sent again for confirmation.

Fails are caused by several factors that are common to both sides of the industry, which can be the result of poor communication, settlement data issues, market forces and market practices.

Communication issues

Communication is probably the most critical facet of the confirmation process and causes most fails. Trades executed and submitted to a clearing corporation run the risk of not being matched if completed close to the allotted trade deadline. If the trade does not meet the deadline, the result will be an unmatched trade and the rectification of this will require human intervention. If a trade is not matched in time, it will settle delivery versus payment (DvP), which negates the cost and risk-mitigation benefits of the netting process.

This problem is experienced mostly on the sell side, because of participation at various clearing utilities. Although some of the larger buy-side firms are members of these organisations, a good majority are not.

Asset managers, meanwhile, interact with the sell side on behalf of many of accounts. For example, asset manager A might manage a hundred sub-accounts that vary among pension, retirement and annuity funds. Trades may be undertaken at an aggregate level and then allocated to one or more sub-accounts.

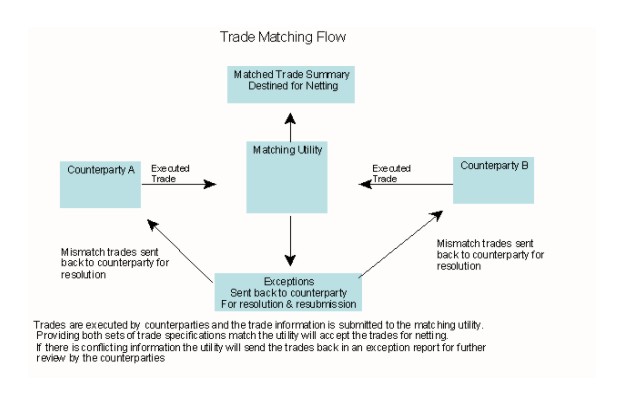

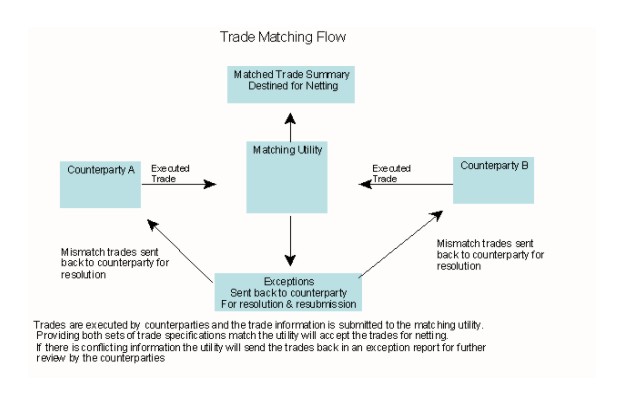

Figure 1 Trade matching flow

Depending on how the allocation of the block trade is communicated to the broker, there may not be enough time to enter the trade allocation before settlement deadlines. These communications are dependent on e-mails, faxes or, in some cases, verbal communication. Even when the process is automated, there can be occasions on which systems or power failures prevent the trade information from being sent in a timely fashion. In addition, these mediums require manual data entry, which is prone to error and can result in trade details being incorrect.

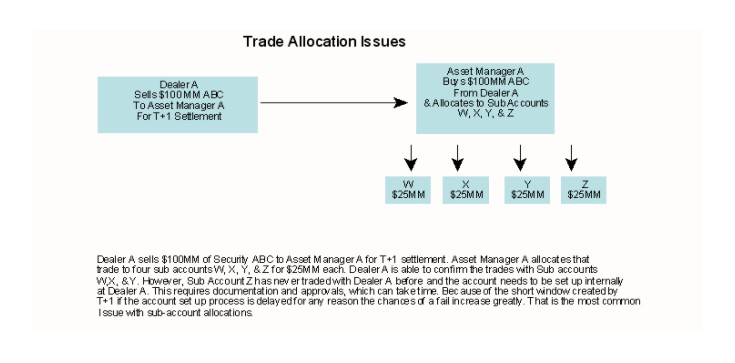

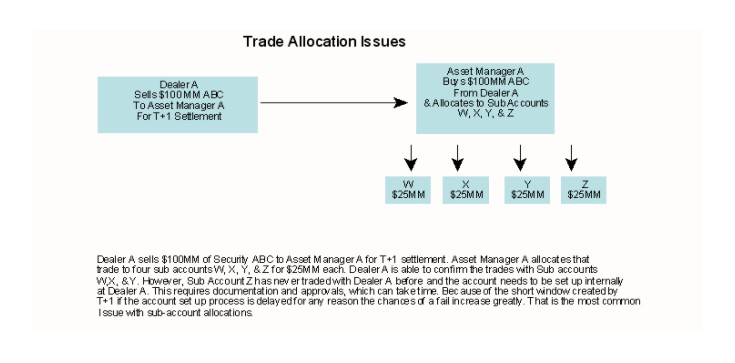

Figure 2 Trade allocation issues

Settlement data issues

Another crucial element of the process is ensuring that the correct settlement details are part of the trade information being sent to the custodian or clearing bank.

In most cases, if a security is delivered to an incorrect depository or custodian, the security will be returned with the appropriate message, provided that there is no matching settlement instruction. There are, however, some occasions on which securities will not be returned until Federal Reserve (Fed) reversal time, which gives the delivering party minimal time in which to determine where the securities should have been sent in the first place and to make the delivery for proper settlement. Inability to do this in a timely manner will cause a fail.

Almost all depositories - such as the Depository Trust Company (DTC), Euroclear, etc - can handle the settlement of many types of security. Government securities, for example, can settle on the Fed book entry system, as well as through the DTC. Sometimes, a security can be set up to settle in the wrong place. There are processes to convert securities from one clearance vehicle to another, but that takes time. This scenario almost always results in at least a one-day fail for the offending firm.

If an existing trade is confirmed and undergoes a modification that is not communicated properly, meanwhile, the result will be a fail, because the trading parties will have differing settlement details and, until those particulars can be worked out, the trade cannot settle.

Market forces

There are forces within the market that are inherent in causing fails. In the summer of 2003, the May 10 Year Note fail problem resulted from demand for the note far outstripping its issue by the Treasury and this set off a pandemic' fail situation.

Securities are borrowed and loaned all the time in the course of firms financing their trading activities. If the counterparty on a financing trade fails to make back the delivery, however, the firm sell on the other side will fail as well. In a similar situation, the counterparty might become insolvent, resulting in a fail back to the lending party - and any pending firm trades will fail as a result.

Market practices

In the course of daily business, there are accepted market practices that can exacerbate fail problems if various conditions exist.

In the MBS pass-through sector of the fixed income world, pools slated for delivery to satisfy TBA trades are routinely pulled back and substituted with similar pools. These substitutions arise from the need to get the right mix of collateral for real estate mortgage investment conduit (REMIC) and collateralised mortgage obligation (CMO) issues, and pulling back pools that have been pledged to a TBA but not yet delivered is common practice. The downside is that such a practice worsens the existing fails in that particular pool. These pool subs are usually part of daisy chains' known as round robins', which may include from as few as three, to many parties. The substitutions are passed around the chain and a great deal of effort is required to clean these fails up.

The main reason for this type of scenario is excessive deal issuance in a particular product and coupon. For example, there might be a heavy demand for FNMA (Federal National Mortgage Association) 6% because a number of firms are issuing REMIC or CMO securities backed by this type of collateral. Another cause for failure that is related to the substitution scenario can be created through the settlement process if a particular security is sold to several different dealers and to an outside party - that is, to a counterparty outside the dealer chain.

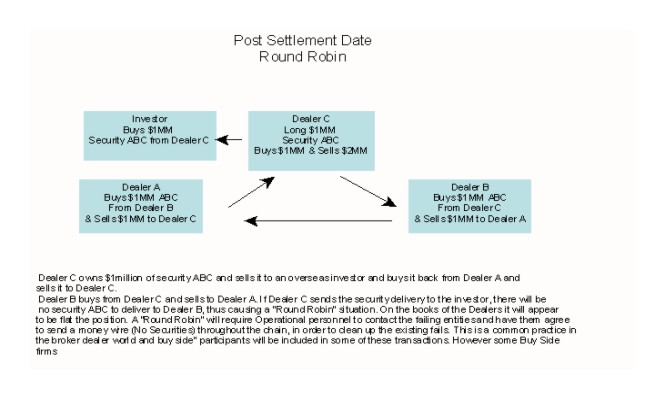

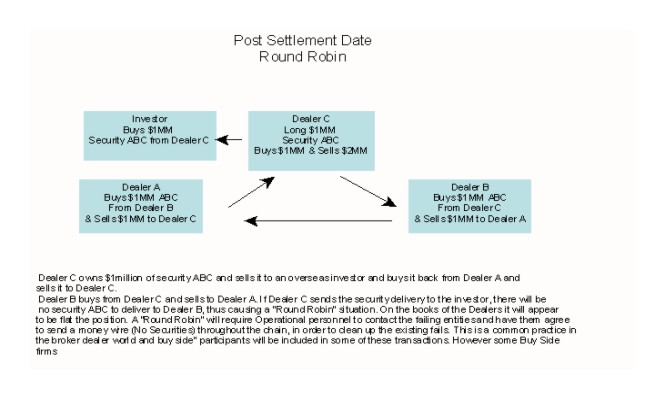

Figure 3 is an example of the most common security flows that might cause a fail and lead to a round robin' scenario.

The final practice-based reason for a fail situation is when one party jams' the other side. This situation is usually the result of a disagreement on certain trade details, or of miscommunication between the trading desk and the operations area. A security will be intentionally delivered just as the Fedwire is closing, which leaves no time for the receiving party to send it back if it does not agree with the settlement details. This type of activity is frowned upon because it has the potential to create animosity, as well as to alter firm relationships - but it still happens.

MARKET INITIATIVES ADDRESSING FAILS

There are several initiatives, some of which are more formal than others, that are currently under way to mitigate fails and to prevent chronic fail situations. The Asset Managers Forum (AMF), Omgeo, TradeWeb and the DTCC are several of the utilities or vendors that are actively seeking to establish themselves in the fail mitigation role by leveraging their products or components of them.

The AMF

The AMF is a division of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). Asset managers convene throughout the year to discuss industry issues and seek to develop best practices through which to accommodate these changes. The AMF has several initiatives under way that are designed to mitigate the risks of failing trades:

- the standard fail report

- standing settlement instructions (SSIs);

- a place of settlement (PSET).

The standard fail report is designed to minimise the different ways of reporting fails. Currently, asset managers receive fail reports from brokers and custodians in various formats, and at various times throughout the day. They may receive files in .pdf, .xls, .txt, or other custom formats that all contain different data fields. Due to this inconsistency, asset managers may use accounting entries as a way to track their fails internally. Each day, as a custodian area sends its accounting statements to the asset managers, a trade will be marked as settled if it is reported on the statement. If no entry is present, the trade is reported as a fail. This works well enough for accounts that settle on an actual basis, indicating a DvP, but an account that is set up to settle on a contractual basis presents different issues. In this scenario, trades are reported settled on settlement date, regardless of whether DvP has occurred. This is done solely for accounting purposes: the customer will receive credit for the securities, although, from a custody point of view, the fail will still exist. When a trade has been failing for a period of time (usually five days), the settlement entry is reversed. Because a trade can fail for a period of time without recognition, fail resolution teams are forced to pursue failed trade data from brokers as well, and this reliance on multiple data sources for accurate fail information can be a burden.

The AMF has created a working group consisting of custodians, brokers, and asset managers that is dedicated to standardising this process. The ultimate goal is to have the fail data provided to asset managers in a consistent format. This will allow asset managers to load the data into an internal system, within which fail resolution teams can view accurate data and eliminate the contractual fail issues. A real-time view of what is actually failing will go a long way in improving best practices and further mitigating chronic fails.

Another working group, meanwhile, is addressing standing settlement instructions (SSIs). Currently, asset managers and brokers maintain delivery instructions internally on databases or spreadsheets. These are communicated to custody banks for proper settlement, but, due to inconsistency and separate record-keeping repositories, there is the opportunity for incorrect instructions that can result in fails. The working group is looking to establish standardised procedures and templates defining how instructions should be communicated.

The third AMF initiative relates to place of settlement (PSET). Trades fail due to a lack of industry protocol in relationship to the place of settlement. Given the various settlement utilities - that is, DTC, Euroclear, etc - two parties engaged in a trade may provide their custodians with differing settlement vehicles. This results in discrepancies in the trade - sometimes referred to as don't knows' (DKs) - because the receiving party does not have the trade set up on the appropriate system and thus has no instructions. The working group is seeking to establish a standard, so that the place of settlement is communicated prior to settlement day and this problem is thereby precluded.

The additional dialogue in which AMF is involved relates to asset managers joining clearing utilities. Buy-side firms face many hurdles before they can take advantage of the benefits that FICC offers. Today, there is no FICC GSD membership category for buy-side firms and, historically, buy-side firms have been either unable or unwilling to adhere to membership requirements, such as posting margin and agreeing to loss allocation. Efforts are under way in the GSD - particularly with prime brokers - to include hedge fund trades as part of the daily netting regimen. Prime brokers can choose to submit their clients' trades for comparison only, or comparison and netting, depending on the prime broker's tolerance for risk. The GSD expects increased participation using this model before year end.

Because asset managers are acting on behalf of various clients, the rules and regulations that they need to follow are very stringent. In theory, their fiduciary responsibilities may conflict with the goals of the netting process. The job of the asset manager is to maximise profit for the client. In order to leverage the advantages offered by the DTCC, there needs to be a substantial investment by the asset manager, which erodes potential profit. Coupled with the intense scrutiny involved in gaining membership and the associated expenses required, most clients do not think that the return is worth the effort.

For example, with some asset managers, settling trades requires that there actually be a DvP, due to rules set forth in the portfolio charter. The goal of netting is to settle cash differences and to keep actual security deliveries to a minimum - and this is the type of hurdle that needs to be cleared to encourage more asset managers to be involved in the netting model.

The margin requirements set forth by the DTCC to maintain the integrity of the mark to market environment require the posting of collateral to accommodate any negative market swings. This type of trade activity, while normal for a broker dealer, is the exception for an asset manager: the need to buy or sell additional collateral could upset the portfolio analytics and create unnecessary losses in the fund.

Most asset managers do not invest heavily in creating an infrastructure to support daily trading activity, especially high-volume activity. Their mantra is one of quality over quantity'. This type of trading does not justify the expenses involved in becoming a netting member. In order to become an FICC participant, there are a number of interfaces and connections that need to be established in addition to the internal software and program changes necessary to route trading activity to the netting utility correctly. There are some sub-accounts within an asset manager that simply cannot justify that type of expense in relation to the portfolio goals.

The most critical goal of the DTCC is risk management. In order to support this goal, there is a huge amount of information involved in becoming a member. The vetting process is very comprehensive and requires a maximum amount of scrutiny. Some asset managers do not want to subject themselves or their clients to this type of review, and will instead shy away from joining the utility - but the dialogue will continue and, hopefully, some of these obstacles will be overcome to allow more asset managers to enjoy the services offered by the DTCC.

Omgeo

The OASYS system operated by Omgeo has provided sub-account allocation information to the equities industry for years. Omgeo has, however, recently embarked on enhancements that will include fixed income products and a broader scope for OASYS. The electronic notification of trading information from an asset manager to a broker is, in most cases, loaded directly into a firm's settlement system. Once these trades have been acknowledged, they are passed through to the appropriate clearing utility for comparison and matching. This straight-through processing (STP) method minimises the chance of error.

TradeWeb

TradeWeb is an online marketplace for an array of fixed income products and derivatives. The online environment for sell-side to buy-side clientele provides an enormous amount of liquidity, which keeps the marketplace functioning in a cohesive manner.

TradeWeb offers a multitude of trading services and up-to-date pricing services. Its platform has handled over US$400bn worth of trading activity in a single day across products.

In addition to the trading platform, TradeWeb offers allocation notification. As mentioned earlier, manual allocations of block trades can be cumbersome and prone to error. Allocations under TradeWeb can be added to a confirmed block trade and sent directly to the broker in an automated fashion. The brokers, in many cases, have this linked to their internal systems and feed the allocations in electronically. Each individual trade will receive its own confirmation, which feeds back to the counterparty, and a trade does not need to be traded in TradeWeb to leverage this functionality.

This electronic platform provides an automated STP environment, which helps to minimise errors on critical trade information, and ensures proper and timely settlement.

The DTCC

The DTCC is the parent company for the FICC, consisting of the GSD and the MBSD (see above). These two netting and comparison utilities are the cornerstone of fail and risk management for the fixed income industry.

During the period between June 2006 and May 2007, the MBSD cleared over US$80tn in TBAs. In the same time frame, its volume of electronic pool notification (EPN) activity exceeded US$8tn. This indicates that over 90 per cent of all TBA trading activity netted through the MBSD and these are trades that, if left to the manual settlement process, would have had the potential to fail, and would have incurred huge manpower and costs. Because of the netting capabilities and processes inherent at the MBSD, that potential is reduced significantly.

The government securities market, meanwhile, is one of the most significant fixed income markets in the world. In the past 12 months, the GSD has compared and matched over US$720tn worth of government securities. The settlement results of this matching and netting are over US$220tn and a reduction in potential fails of over 70 per cent. In relation to this market, which represents one of the most liquid financial instruments, short of cash, this significant reduction of fail risk is a tremendous asset to the marketplace.

The GSD of FICC operates a daily net out as opposed to its MBS counterpart, which runs its netting processes four times a month to coincide with approved settlement dates. The size and trading protocol (T+1) within the government securities industry requires that trades be netted out on a daily basis, which netting leaves each participant with its net trading position on a given settlement day for a given security. These include all transactions, whether they are firm or financing trades. Such netting mitigates fail risk by eliminating those trades from potential settlement activity for a given day: the fewer trades there are to settle, the less risk of a fail.

In order to alleviate the pressure of the large amount of fails during the ten-year note fail problem of 2003, GSD started re-netting the open fails on the system for only that particular issue. This resulted in a number of trades being taken out of the process and a reduction in the number of open fails.

Because the process proved to be effective in alleviating the problem, the GSD and its participants decided to phase it into the everyday processing for all of the securities it supports. On the evening of 22nd September, 2006, the GSD went live with the fail netting process across all Treasury and agency products. This implementation effectively eliminates almost all fails in much the same way as does continuous net settlement in the equities markets.

Up until the early 1990s, telephone and fax were the prominent methods of MBS pool notification. The manual nature of this communication contributed to a significant amount of fails for the industry: hard-to-read faxes, miscommunication during calls and transposed numbers during data entry resulted in the wrong pool information being input into settlement systems. Electronic pool notification (EPN) lines, however, were always open, solving the issue of busy signals on telephones and faxes at the peak time prior to the 3 pm cut-off point by which information must be passed.

Through the efforts of MBSD and the participant community, EPN is now the pool notification standard. The automatic interface, which is controlled by MBSD, has created an environment that, for the most part, has eliminated numerous issues inherent in the manual environment. The fact that a recipient does not have to be available to receive pool information, which is supplemented with time stamps for the sender, has dramatically reduced the number of fails that were experienced up until the early 1990s.

One of the newer innovations going live at MBSD is the matching of pool-poolspecific trades. This enables all of the characteristics of a pool to be determined and communicated at trade execution. With this new service being offered by the MBSD, the increasing volume of specified pool trades should reduce fails, because of the fact that the matching process is completed prior to settlement.

The goal of the MBSD is, ultimately, to become a central counterparty (CCP) to all pool activity, whether the result of TBA pool allocations or of specified pool trading. Daily pool netting will greatly reduce the number of pool settlements and, by extension, the risk for fails will subside accordingly.

Currently, fails to deliver or fails to receive can be part of larger daisy chains', and it might take weeks before these chains are identified and cleaned up through either net money exchanges or collateral substitutions. Pool netting will reduce the costs of open fails substantially, as well as the risk of fails; it will also decrease margin requirements and free up firm capital to pursue revenue-generating transactions.

MARKET PRACTICES ADDRESSING FAILS

These many market initiatives have gone a long way in helping the industry to manage the risks that come with unsettled trades. On both sides of the industry, however, there are practices that - although not formalised - have become inherent in fail processing and play a major part in cleaning up open trades that have not settled.

Round robins (MBS)

Round robins are identified through daisy chains of failing pools. These chains can number anywhere from three participants, to literally dozens.

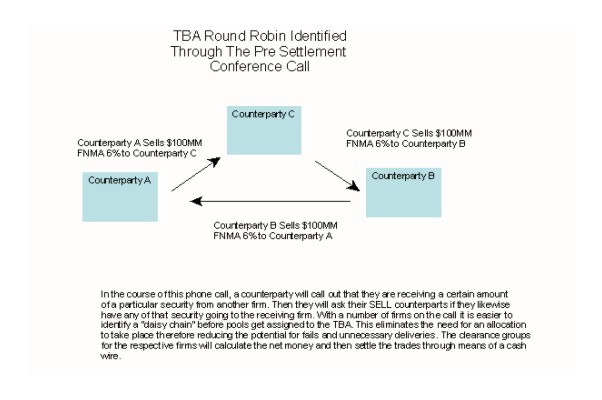

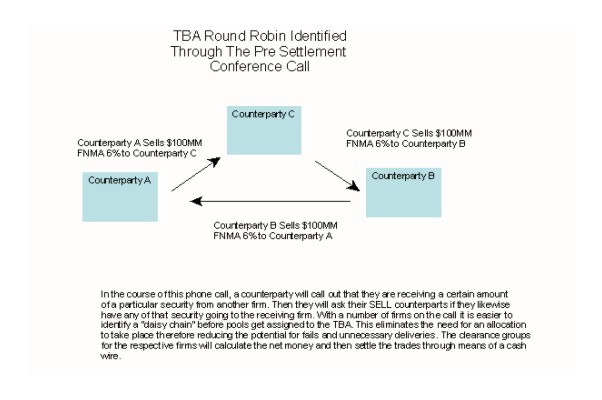

Figure 4 TBA round robin' identified through the pre-settlement conference call

As Figure 4 shows, the chain involves buys and sells, within which various participants in the chain have pieces of the security and are awaiting failing bonds to deliver out fails on the sell side. The inability for one participant to make a delivery creates a logjam for all of the downstream customers.

In the last few years, the dealer community has initiated a round robin call that takes place on the MBS 48-hour day. The call takes place in the morning when all settlement balance order (SBO) netout trades have been identified and broker trades have been given up. Attempts are made to identify the parties in these daisy chains in the current coupon securities. In this way, these calls reduce the number of TBA trades to be allocated and reduce potential fail risk.

After the settlement period has passed, however, most firms will begin the process of confirming opening fails with counterparties. It is through this process that the communication starts to take place to identify these round robins and then to work them out. The actual clearance process will be more difficult as the number of firms in the daisy chain grows.

Buy-in rules

In addition to the unwritten practices, there are established rules and guidelines within the industry that deal with failing trades and provide a measure of protection to the parties involved.

Buy-in procedures have been established to handle protracted fails within the MBS and government markets. These give the party failing to receive recourse to force a settlement of the trade, whether that involves receiving the actual securities or cash compensation for any losses suffered as a result of the fail.

In relation to the MBS market, the current rule states that, when a brokerdealer is being failed by a non-brokerdealer for a period of greater than 60 days, a buy-in must be initiated for the failing security. In the MBS sector, a similar security or MBS pool of similar characteristics to the failing item can be substituted, as long as both parties agree.

In relation to the government market, the current rule states that, when a broker-dealer is being failed to by a non-broker-dealer for a period of greater than 30 days, a buy-in must be initiated for the failing security. Unlike in the MBS sector, the actual failing security can be bought in. This is due to the liquidity and amount of issues that circulate in the Treasury markets as opposed to those that circulate in the MBS market.

Capital charges

Capital charges relate to the criteria set forth in the reserve formula for customer protection purposes. When broker-dealer firms have fails to receive on the books from customers, customer protection rules require that capital be set aside to cover a default on the receive side. After calculating the amount of money needed to be reserved under the customer protection reserve formulas, a firm will have to commit its own funds to cover any potential loss - funds that could have been used to generate revenue.

CONCLUSION

Over the years, the industry, as a whole, has adopted many practices and procedures with which to operate in a controlled environment and limit the amount of risk to which participants expose themselves on a daily basis.

As we have discussed, DTCC and its subsidiaries - the GSD and the MBSD - have contributed greatly to mitigating fail risk by virtue of their netting processes. These are vehicles that are constantly evolving, evidenced by fail renetting on the GSD side, which was borne from the fail issues experienced back in the summer of 2003 and the MBSD initiative in pursuing the CCP model.

These initiatives all show that financial markets do not stand still when it comes to addressing problems facing the industry and are constantly searching for new solutions. The reasons for fails and how they are resolved are numerous; many of the current guidelines in place are the result of exacerbated fail problems. This is an example of how adept and creative the industry is in reacting to a crisis - and the market's ability to adapt to problems is crucial in reducing the number of fails.

Many firms have developed internal procedures to assist in mitigating the fail problems that arise from factors that they can control in their own daily businesses. These controls include the fail confirmation process, under which fails are confirmed with counterparties on a daily basis to ensure that all parties are on the same page. There is, then, a tremendous amount of pressure on the sales desk and operations to ensure that all settlement delivery instructions are updated on a regular basis to prevent delivery problems that might result in fails.

Trade confirmation and matching utilities are a key component of making sure that the latest information is readily available to market participants to ensure the timely flow of securities once they get to the settlement phase.

The mitigation of fail risk is crucial to the survival of the industry and its credibility. It is this knowledge that spurs it on to find new ways to deal with fails and, hopefully, to achieve an environment within which there are no fails. As difficult as that might sound, it remains a goal worth pursuing - but until that time comes, fails will continue to be as certain as death and taxes'.

NOTE

This paper reflects the views and opinions of the individual authors and not neccessarily those of their employers or other organisations with which they are associated.

REFERENCES

(1) The FICC is made up of the Government Securities Division (GSD), formerly known as the Government Securities Clearing Corporation (GSCC), and the Mortgage-Backed Securities Division (MBSD), formerly known as the Mortgage-Backed Securities Clearing Corporation (MBSCC). Both entities now fall under the DTCC umbrella.

(2) The TBA trade is much like a futures trade: settlement dates can be scheduled days, weeks, even months in the The seller is required to announce pools that will be delivered to satisfy trade at least 48 hours in advance settlement date. Failure to do so result in delivery being pushed out another 24 hours. For the purposes calculating net proceeds, however, settlement date never changes.

This site, like many others, uses small files called cookies to customize your experience. Cookies appear to be blocked on this browser. Please consider allowing cookies so that you can enjoy more content across globalcustody.net.

How do I enable cookies in my browser?

Internet Explorer

1. Click the Tools button (or press ALT and T on the keyboard), and then click Internet Options.

2. Click the Privacy tab

3. Move the slider away from 'Block all cookies' to a setting you're comfortable with.

Firefox

1. At the top of the Firefox window, click on the Tools menu and select Options...

2. Select the Privacy panel.

3. Set Firefox will: to Use custom settings for history.

4. Make sure Accept cookies from sites is selected.

Safari Browser

1. Click Safari icon in Menu Bar

2. Click Preferences (gear icon)

3. Click Security icon

4. Accept cookies: select Radio button "only from sites I visit"

Chrome

1. Click the menu icon to the right of the address bar (looks like 3 lines)

2. Click Settings

3. Click the "Show advanced settings" tab at the bottom

4. Click the "Content settings..." button in the Privacy section

5. At the top under Cookies make sure it is set to "Allow local data to be set (recommended)"

Opera

1. Click the red O button in the upper left hand corner

2. Select Settings -> Preferences

3. Select the Advanced Tab

4. Select Cookies in the list on the left side

5. Set it to "Accept cookies" or "Accept cookies only from the sites I visit"

6. Click OK

Christopher Marzullo is Senior Manager - Fixed Income Middle Office of Lord Abbett, LLC, which he joined in April 2002, initially as supervisor. Prior to joining Lord Abbett, LLC, Christopher was at Nomura Securities International, from April 1996 to April 2002. He began in that organisation in clearance settling trades on the Fedwire system and with the Depository Trust Company (DTC), also backing up MBS allocations and MBSCC groups, and then moved to several desks including repo, government/agency, and pass-throughs/CMOs. Prior to joining Nomura Securities, Christopher had been at Donaldson, Lufkin and Jenrette, from January 1994 to April 1996, beginning his career in MBS allocations and clearance. He is a graduate of Bernard Baruch College, City University of New York, and also has a Series 7 licence. Christopher is a member of committees in the Asset Managers Forum (AMF) that work towards alleviating fails and overdraft instances.

Peter Kelly was a director in fixed income operations with Nomura Securities when this paper was written. He was with Nomura from November 1995. His responsibilities included managing the residential and commercial mortgage groups, which included principal and interest (P&I) processing, accrual reconciliation and trade support. Throughout his tenure at Nomura, Peter managed mortgage-backed security (MBS) allocations, MBS Clearing Corporation (MBSCC) processing, collateralised mortgage obligation (CMO) operations, all of the fixed income clearance groups and the security master functions. Peter started his career in 1988 with JPMorgan in corporate finance operations. He managed the processing for the special loan portfolio, as well as for the money transfer investigations unit. In 1991, he transferred to JPMorgan Securities and became supervisor for the MBS allocations group, in which role he continued until he left the firm in 1995. Peter has a degree in economics from St Francis College and a Master of Business Administration degree in finance from Pace University. He is currently pursuing other consulting opportunities.

Frederick Lipinski is a director in fixed income operations at Nomura Securities. He started in the company in fixed income settlements and was transferred to fixed income trade entry; his responsibilities include MBS, CMO derivatives, government, repo, corporate and whole loan trade support and settlements, as well as whole loan P&I collections. He has been with Nomura since January 1989. Prior to Nomura, Frederick worked at Salomon Brothers in equity fail control, before being transferred to fixed income settlements and repo trade support. He is chairman of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) Government Operations Committee and a member of the Corporate Operations Committee. Frederick has a degree in marketing from Middlesex College.

ABSTRACT

The following paper is written by representatives from the buy and sell sides of the US fixed income securities industry. Its focus is on fail issues that are pertinent to the US markets. The authors are members of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), an industry group that focuses on the needs and problems of the US fixed income markets. In the course of this paper, the authors will show the reasons why fails occur, as well as some of the reactive and preventative actions that may be taken to minimise the number of fails. The paper will also touch on some of the initiatives that have commenced within the industry towards managing fail risk and minimising the number of fails, as well as the number of actual trades that get settled during the course of an average business day. By providing a point of view from both sides of the market, the paper aims to offer a fuller understanding of the practices and procedures in addressing fail issues that vary on each side of the business. The reader will also take away knowledge of the industry's ongoing projects to reduce further the number of fails and the associated risk.

Keywords: fails, Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC), asset manager, broker, round robin, netting

INTRODUCTION

To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin: In this world, nothing is certain but death and taxes.' Had Franklin worked in the securities industry, he might have added fails' to his list of certainties.

Recognising the inevitability of fails and the impossibility of their elimination, the industry has focused instead on minimising them. At the end of each day, most institutional market participants will have fails on their books. These failing items will be confirmed with the parties involved and settled within a day or two. There have, however, been situations in which chronic fails have plagued the industry: the days following 11th September, 2001, for example, and the summer of 2003.

The attack on the World Trade Center and damage to the downtown area of New York created a situation in which trading records were destroyed, and communications were knocked out between the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC)1 and its participant population, as well as clearing banks and their customers. The combination of destroyed records and connectivity problems contributed to the FICC having almost US$440bn worth of government security fails on 12th September, 2001. The numbers gradually decreased as the industry started getting back on line and, by the end of that week, the figure had fallen to around US$90bn - but it took many weeks for affected firms to reconcile their fail issues. The US Treasury actually expanded an existing note issue from US$12bn to US$18bn to help to facilitate deliveries.

In early July 2003, the US Treasury, May 2013, ten-year note experienced excessive borrowing demand, which drove the repo rate for specials to almost zero. This situation spread into settlement fails, which caused buyers of the issue to become lenders, rather than simply holders, of the securities. A concerted effort by the Bond Market Association (BMA), the FICC and their members to identify round robins, re-net failing trades and other initiatives helped, eventually, to eliminate what had become a serious fail issue.

Fails cause enough angst for risk managers - but, while the industry worked feverishly to get things back to normal, these two particular episodes caused risk managers to double up on the antacids. The industry is always trying to find new ways to mitigate fail risk, and these examples show how quickly a systemic failure can spiral out of control and the effort that is required to get things right.

The two major players in the US markets are the broker-dealer side - known as the sell side' - and the asset manager community (hedge funds, pension funds, insurance companies, etc) - known as the buy side'. The goal of this paper is to illustrate the issues associated with fails and how these two sides of the industry attempt to minimise those issues.

A fail occurs when a security transaction does not clear on the settlement or contract date. When a trade is executed, the information is disseminated to the counterparty or any interested party that the client has assigned - that is, a custodian bank. This flow of information is critical to assure proper settlement. The inability to settle a trade carries consequences and creates problems throughout the firms involved. There are various safeguards in place to help to mitigate these issues and to eliminate them quickly so that they do not become major problems.

When a trade fails to settle, the firms involved do not receive cash that could have been invested in revenue-generating transactions; instead, a firm will have to borrow that cash to finance those activities. It is interesting to note that the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) pass-through market - also known as the to be announced' (TBA) market2 - is unique in that it allows participants the chance to fail twice: once during the pool information phase of the transaction and once during the actual settlement phase. The consequence of the fail is that the purchase of the pools is financed for a day or two before the transactional proceeds from the respective delivery are received.

There are many risks and issues that come with a failing transaction that can have serious repercussions if not carefully monitored. Some of the risks involved to a firm when trades fail to settle in a timely fashion are as follows.

Counterparty credit risk

Counterparty credit risk occurs when the failing seller goes out of business before the trade settles, resulting in a loss to the buyer. This requires the buyer to go out and purchase that position, resulting in a huge loss if there has been a substantial market movement from the original trade price. This risk also involves the cost of litigation, due to bankruptcy of the firm failing to receive so that it may recoup any losses.

Ancillary costs to broker-dealers

For broker-dealers, there is a cost associated with following the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules that require firms to set aside capital to cover the cost of a failing trade. Any firm deliveries that fail for more than four business days are subject to capital requirements. Fails of more than 30 calendar days also require capital to be set aside that might have been used instead to finance trading activity.

Customer relationship issues

Fails have the potential to create customer relationship issues: customers tend to get concerned when they do not receive their bonds on the contractual settlement date; some entities, such as foreign central banks, will require a guarantee of delivery. Failure to deliver a bond might result in the customer refusing to do further business with the offending firm.

THE TRADE CONFIRMATION PROCESS

Almost all firms follow procedures to ensure that, when a trade is made, each side has the correct information to effect proper settlement: one side gets the money; the other side gets the securities.

In theory, the trade process is easy - but, in practice, there can be problems. Trade confirmation, for example, can be handled in several ways. In order to process a trade confirmation, a firm must obtain the client's account information, which includes standard settlement instructions (SSIs). A client may have many custodians for transaction processing or only one, which choice is usually dictated by the product and the way in which it settles. The most common way in which to confirm a trade is a mailed document featuring all trade details:

- trade date

- settlement date;

- price

- Committee on Uniform Security Identification Procedures (CUSIP) and security details;

- in what capacity the counterparty is acting (principal or agent).

Once the correct information is determined, the necessary amendments are made to address these exceptions and the trades are sent again for confirmation.

Fails are caused by several factors that are common to both sides of the industry, which can be the result of poor communication, settlement data issues, market forces and market practices.

Communication issues

Communication is probably the most critical facet of the confirmation process and causes most fails. Trades executed and submitted to a clearing corporation run the risk of not being matched if completed close to the allotted trade deadline. If the trade does not meet the deadline, the result will be an unmatched trade and the rectification of this will require human intervention. If a trade is not matched in time, it will settle delivery versus payment (DvP), which negates the cost and risk-mitigation benefits of the netting process.

This problem is experienced mostly on the sell side, because of participation at various clearing utilities. Although some of the larger buy-side firms are members of these organisations, a good majority are not.

Asset managers, meanwhile, interact with the sell side on behalf of many of accounts. For example, asset manager A might manage a hundred sub-accounts that vary among pension, retirement and annuity funds. Trades may be undertaken at an aggregate level and then allocated to one or more sub-accounts.

Figure 1 Trade matching flow

Depending on how the allocation of the block trade is communicated to the broker, there may not be enough time to enter the trade allocation before settlement deadlines. These communications are dependent on e-mails, faxes or, in some cases, verbal communication. Even when the process is automated, there can be occasions on which systems or power failures prevent the trade information from being sent in a timely fashion. In addition, these mediums require manual data entry, which is prone to error and can result in trade details being incorrect.

Figure 2 Trade allocation issues

Settlement data issues

Another crucial element of the process is ensuring that the correct settlement details are part of the trade information being sent to the custodian or clearing bank.

In most cases, if a security is delivered to an incorrect depository or custodian, the security will be returned with the appropriate message, provided that there is no matching settlement instruction. There are, however, some occasions on which securities will not be returned until Federal Reserve (Fed) reversal time, which gives the delivering party minimal time in which to determine where the securities should have been sent in the first place and to make the delivery for proper settlement. Inability to do this in a timely manner will cause a fail.

Almost all depositories - such as the Depository Trust Company (DTC), Euroclear, etc - can handle the settlement of many types of security. Government securities, for example, can settle on the Fed book entry system, as well as through the DTC. Sometimes, a security can be set up to settle in the wrong place. There are processes to convert securities from one clearance vehicle to another, but that takes time. This scenario almost always results in at least a one-day fail for the offending firm.

If an existing trade is confirmed and undergoes a modification that is not communicated properly, meanwhile, the result will be a fail, because the trading parties will have differing settlement details and, until those particulars can be worked out, the trade cannot settle.

Market forces

There are forces within the market that are inherent in causing fails. In the summer of 2003, the May 10 Year Note fail problem resulted from demand for the note far outstripping its issue by the Treasury and this set off a pandemic' fail situation.

Securities are borrowed and loaned all the time in the course of firms financing their trading activities. If the counterparty on a financing trade fails to make back the delivery, however, the firm sell on the other side will fail as well. In a similar situation, the counterparty might become insolvent, resulting in a fail back to the lending party - and any pending firm trades will fail as a result.

Market practices

In the course of daily business, there are accepted market practices that can exacerbate fail problems if various conditions exist.

In the MBS pass-through sector of the fixed income world, pools slated for delivery to satisfy TBA trades are routinely pulled back and substituted with similar pools. These substitutions arise from the need to get the right mix of collateral for real estate mortgage investment conduit (REMIC) and collateralised mortgage obligation (CMO) issues, and pulling back pools that have been pledged to a TBA but not yet delivered is common practice. The downside is that such a practice worsens the existing fails in that particular pool. These pool subs are usually part of daisy chains' known as round robins', which may include from as few as three, to many parties. The substitutions are passed around the chain and a great deal of effort is required to clean these fails up.

The main reason for this type of scenario is excessive deal issuance in a particular product and coupon. For example, there might be a heavy demand for FNMA (Federal National Mortgage Association) 6% because a number of firms are issuing REMIC or CMO securities backed by this type of collateral. Another cause for failure that is related to the substitution scenario can be created through the settlement process if a particular security is sold to several different dealers and to an outside party - that is, to a counterparty outside the dealer chain.

Figure 3 is an example of the most common security flows that might cause a fail and lead to a round robin' scenario.

The final practice-based reason for a fail situation is when one party jams' the other side. This situation is usually the result of a disagreement on certain trade details, or of miscommunication between the trading desk and the operations area. A security will be intentionally delivered just as the Fedwire is closing, which leaves no time for the receiving party to send it back if it does not agree with the settlement details. This type of activity is frowned upon because it has the potential to create animosity, as well as to alter firm relationships - but it still happens.

MARKET INITIATIVES ADDRESSING FAILS

There are several initiatives, some of which are more formal than others, that are currently under way to mitigate fails and to prevent chronic fail situations. The Asset Managers Forum (AMF), Omgeo, TradeWeb and the DTCC are several of the utilities or vendors that are actively seeking to establish themselves in the fail mitigation role by leveraging their products or components of them.

The AMF

The AMF is a division of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). Asset managers convene throughout the year to discuss industry issues and seek to develop best practices through which to accommodate these changes. The AMF has several initiatives under way that are designed to mitigate the risks of failing trades:

- the standard fail report

- standing settlement instructions (SSIs);

- a place of settlement (PSET).

The standard fail report is designed to minimise the different ways of reporting fails. Currently, asset managers receive fail reports from brokers and custodians in various formats, and at various times throughout the day. They may receive files in .pdf, .xls, .txt, or other custom formats that all contain different data fields. Due to this inconsistency, asset managers may use accounting entries as a way to track their fails internally. Each day, as a custodian area sends its accounting statements to the asset managers, a trade will be marked as settled if it is reported on the statement. If no entry is present, the trade is reported as a fail. This works well enough for accounts that settle on an actual basis, indicating a DvP, but an account that is set up to settle on a contractual basis presents different issues. In this scenario, trades are reported settled on settlement date, regardless of whether DvP has occurred. This is done solely for accounting purposes: the customer will receive credit for the securities, although, from a custody point of view, the fail will still exist. When a trade has been failing for a period of time (usually five days), the settlement entry is reversed. Because a trade can fail for a period of time without recognition, fail resolution teams are forced to pursue failed trade data from brokers as well, and this reliance on multiple data sources for accurate fail information can be a burden.

The AMF has created a working group consisting of custodians, brokers, and asset managers that is dedicated to standardising this process. The ultimate goal is to have the fail data provided to asset managers in a consistent format. This will allow asset managers to load the data into an internal system, within which fail resolution teams can view accurate data and eliminate the contractual fail issues. A real-time view of what is actually failing will go a long way in improving best practices and further mitigating chronic fails.

Another working group, meanwhile, is addressing standing settlement instructions (SSIs). Currently, asset managers and brokers maintain delivery instructions internally on databases or spreadsheets. These are communicated to custody banks for proper settlement, but, due to inconsistency and separate record-keeping repositories, there is the opportunity for incorrect instructions that can result in fails. The working group is looking to establish standardised procedures and templates defining how instructions should be communicated.

The third AMF initiative relates to place of settlement (PSET). Trades fail due to a lack of industry protocol in relationship to the place of settlement. Given the various settlement utilities - that is, DTC, Euroclear, etc - two parties engaged in a trade may provide their custodians with differing settlement vehicles. This results in discrepancies in the trade - sometimes referred to as don't knows' (DKs) - because the receiving party does not have the trade set up on the appropriate system and thus has no instructions. The working group is seeking to establish a standard, so that the place of settlement is communicated prior to settlement day and this problem is thereby precluded.

The additional dialogue in which AMF is involved relates to asset managers joining clearing utilities. Buy-side firms face many hurdles before they can take advantage of the benefits that FICC offers. Today, there is no FICC GSD membership category for buy-side firms and, historically, buy-side firms have been either unable or unwilling to adhere to membership requirements, such as posting margin and agreeing to loss allocation. Efforts are under way in the GSD - particularly with prime brokers - to include hedge fund trades as part of the daily netting regimen. Prime brokers can choose to submit their clients' trades for comparison only, or comparison and netting, depending on the prime broker's tolerance for risk. The GSD expects increased participation using this model before year end.

Because asset managers are acting on behalf of various clients, the rules and regulations that they need to follow are very stringent. In theory, their fiduciary responsibilities may conflict with the goals of the netting process. The job of the asset manager is to maximise profit for the client. In order to leverage the advantages offered by the DTCC, there needs to be a substantial investment by the asset manager, which erodes potential profit. Coupled with the intense scrutiny involved in gaining membership and the associated expenses required, most clients do not think that the return is worth the effort.

For example, with some asset managers, settling trades requires that there actually be a DvP, due to rules set forth in the portfolio charter. The goal of netting is to settle cash differences and to keep actual security deliveries to a minimum - and this is the type of hurdle that needs to be cleared to encourage more asset managers to be involved in the netting model.

The margin requirements set forth by the DTCC to maintain the integrity of the mark to market environment require the posting of collateral to accommodate any negative market swings. This type of trade activity, while normal for a broker dealer, is the exception for an asset manager: the need to buy or sell additional collateral could upset the portfolio analytics and create unnecessary losses in the fund.

Most asset managers do not invest heavily in creating an infrastructure to support daily trading activity, especially high-volume activity. Their mantra is one of quality over quantity'. This type of trading does not justify the expenses involved in becoming a netting member. In order to become an FICC participant, there are a number of interfaces and connections that need to be established in addition to the internal software and program changes necessary to route trading activity to the netting utility correctly. There are some sub-accounts within an asset manager that simply cannot justify that type of expense in relation to the portfolio goals.

The most critical goal of the DTCC is risk management. In order to support this goal, there is a huge amount of information involved in becoming a member. The vetting process is very comprehensive and requires a maximum amount of scrutiny. Some asset managers do not want to subject themselves or their clients to this type of review, and will instead shy away from joining the utility - but the dialogue will continue and, hopefully, some of these obstacles will be overcome to allow more asset managers to enjoy the services offered by the DTCC.

Omgeo

The OASYS system operated by Omgeo has provided sub-account allocation information to the equities industry for years. Omgeo has, however, recently embarked on enhancements that will include fixed income products and a broader scope for OASYS. The electronic notification of trading information from an asset manager to a broker is, in most cases, loaded directly into a firm's settlement system. Once these trades have been acknowledged, they are passed through to the appropriate clearing utility for comparison and matching. This straight-through processing (STP) method minimises the chance of error.

TradeWeb

TradeWeb is an online marketplace for an array of fixed income products and derivatives. The online environment for sell-side to buy-side clientele provides an enormous amount of liquidity, which keeps the marketplace functioning in a cohesive manner.

TradeWeb offers a multitude of trading services and up-to-date pricing services. Its platform has handled over US$400bn worth of trading activity in a single day across products.

In addition to the trading platform, TradeWeb offers allocation notification. As mentioned earlier, manual allocations of block trades can be cumbersome and prone to error. Allocations under TradeWeb can be added to a confirmed block trade and sent directly to the broker in an automated fashion. The brokers, in many cases, have this linked to their internal systems and feed the allocations in electronically. Each individual trade will receive its own confirmation, which feeds back to the counterparty, and a trade does not need to be traded in TradeWeb to leverage this functionality.

This electronic platform provides an automated STP environment, which helps to minimise errors on critical trade information, and ensures proper and timely settlement.

The DTCC

The DTCC is the parent company for the FICC, consisting of the GSD and the MBSD (see above). These two netting and comparison utilities are the cornerstone of fail and risk management for the fixed income industry.

During the period between June 2006 and May 2007, the MBSD cleared over US$80tn in TBAs. In the same time frame, its volume of electronic pool notification (EPN) activity exceeded US$8tn. This indicates that over 90 per cent of all TBA trading activity netted through the MBSD and these are trades that, if left to the manual settlement process, would have had the potential to fail, and would have incurred huge manpower and costs. Because of the netting capabilities and processes inherent at the MBSD, that potential is reduced significantly.

The government securities market, meanwhile, is one of the most significant fixed income markets in the world. In the past 12 months, the GSD has compared and matched over US$720tn worth of government securities. The settlement results of this matching and netting are over US$220tn and a reduction in potential fails of over 70 per cent. In relation to this market, which represents one of the most liquid financial instruments, short of cash, this significant reduction of fail risk is a tremendous asset to the marketplace.

The GSD of FICC operates a daily net out as opposed to its MBS counterpart, which runs its netting processes four times a month to coincide with approved settlement dates. The size and trading protocol (T+1) within the government securities industry requires that trades be netted out on a daily basis, which netting leaves each participant with its net trading position on a given settlement day for a given security. These include all transactions, whether they are firm or financing trades. Such netting mitigates fail risk by eliminating those trades from potential settlement activity for a given day: the fewer trades there are to settle, the less risk of a fail.

In order to alleviate the pressure of the large amount of fails during the ten-year note fail problem of 2003, GSD started re-netting the open fails on the system for only that particular issue. This resulted in a number of trades being taken out of the process and a reduction in the number of open fails.

Because the process proved to be effective in alleviating the problem, the GSD and its participants decided to phase it into the everyday processing for all of the securities it supports. On the evening of 22nd September, 2006, the GSD went live with the fail netting process across all Treasury and agency products. This implementation effectively eliminates almost all fails in much the same way as does continuous net settlement in the equities markets.

Up until the early 1990s, telephone and fax were the prominent methods of MBS pool notification. The manual nature of this communication contributed to a significant amount of fails for the industry: hard-to-read faxes, miscommunication during calls and transposed numbers during data entry resulted in the wrong pool information being input into settlement systems. Electronic pool notification (EPN) lines, however, were always open, solving the issue of busy signals on telephones and faxes at the peak time prior to the 3 pm cut-off point by which information must be passed.

Through the efforts of MBSD and the participant community, EPN is now the pool notification standard. The automatic interface, which is controlled by MBSD, has created an environment that, for the most part, has eliminated numerous issues inherent in the manual environment. The fact that a recipient does not have to be available to receive pool information, which is supplemented with time stamps for the sender, has dramatically reduced the number of fails that were experienced up until the early 1990s.

One of the newer innovations going live at MBSD is the matching of pool-poolspecific trades. This enables all of the characteristics of a pool to be determined and communicated at trade execution. With this new service being offered by the MBSD, the increasing volume of specified pool trades should reduce fails, because of the fact that the matching process is completed prior to settlement.

The goal of the MBSD is, ultimately, to become a central counterparty (CCP) to all pool activity, whether the result of TBA pool allocations or of specified pool trading. Daily pool netting will greatly reduce the number of pool settlements and, by extension, the risk for fails will subside accordingly.

Currently, fails to deliver or fails to receive can be part of larger daisy chains', and it might take weeks before these chains are identified and cleaned up through either net money exchanges or collateral substitutions. Pool netting will reduce the costs of open fails substantially, as well as the risk of fails; it will also decrease margin requirements and free up firm capital to pursue revenue-generating transactions.

MARKET PRACTICES ADDRESSING FAILS

These many market initiatives have gone a long way in helping the industry to manage the risks that come with unsettled trades. On both sides of the industry, however, there are practices that - although not formalised - have become inherent in fail processing and play a major part in cleaning up open trades that have not settled.

Round robins (MBS)

Round robins are identified through daisy chains of failing pools. These chains can number anywhere from three participants, to literally dozens.

Figure 4 TBA round robin' identified through the pre-settlement conference call

As Figure 4 shows, the chain involves buys and sells, within which various participants in the chain have pieces of the security and are awaiting failing bonds to deliver out fails on the sell side. The inability for one participant to make a delivery creates a logjam for all of the downstream customers.

In the last few years, the dealer community has initiated a round robin call that takes place on the MBS 48-hour day. The call takes place in the morning when all settlement balance order (SBO) netout trades have been identified and broker trades have been given up. Attempts are made to identify the parties in these daisy chains in the current coupon securities. In this way, these calls reduce the number of TBA trades to be allocated and reduce potential fail risk.

After the settlement period has passed, however, most firms will begin the process of confirming opening fails with counterparties. It is through this process that the communication starts to take place to identify these round robins and then to work them out. The actual clearance process will be more difficult as the number of firms in the daisy chain grows.

Buy-in rules

In addition to the unwritten practices, there are established rules and guidelines within the industry that deal with failing trades and provide a measure of protection to the parties involved.

Buy-in procedures have been established to handle protracted fails within the MBS and government markets. These give the party failing to receive recourse to force a settlement of the trade, whether that involves receiving the actual securities or cash compensation for any losses suffered as a result of the fail.

In relation to the MBS market, the current rule states that, when a brokerdealer is being failed by a non-brokerdealer for a period of greater than 60 days, a buy-in must be initiated for the failing security. In the MBS sector, a similar security or MBS pool of similar characteristics to the failing item can be substituted, as long as both parties agree.

In relation to the government market, the current rule states that, when a broker-dealer is being failed to by a non-broker-dealer for a period of greater than 30 days, a buy-in must be initiated for the failing security. Unlike in the MBS sector, the actual failing security can be bought in. This is due to the liquidity and amount of issues that circulate in the Treasury markets as opposed to those that circulate in the MBS market.

Capital charges

Capital charges relate to the criteria set forth in the reserve formula for customer protection purposes. When broker-dealer firms have fails to receive on the books from customers, customer protection rules require that capital be set aside to cover a default on the receive side. After calculating the amount of money needed to be reserved under the customer protection reserve formulas, a firm will have to commit its own funds to cover any potential loss - funds that could have been used to generate revenue.

CONCLUSION

Over the years, the industry, as a whole, has adopted many practices and procedures with which to operate in a controlled environment and limit the amount of risk to which participants expose themselves on a daily basis.

As we have discussed, DTCC and its subsidiaries - the GSD and the MBSD - have contributed greatly to mitigating fail risk by virtue of their netting processes. These are vehicles that are constantly evolving, evidenced by fail renetting on the GSD side, which was borne from the fail issues experienced back in the summer of 2003 and the MBSD initiative in pursuing the CCP model.

These initiatives all show that financial markets do not stand still when it comes to addressing problems facing the industry and are constantly searching for new solutions. The reasons for fails and how they are resolved are numerous; many of the current guidelines in place are the result of exacerbated fail problems. This is an example of how adept and creative the industry is in reacting to a crisis - and the market's ability to adapt to problems is crucial in reducing the number of fails.

Many firms have developed internal procedures to assist in mitigating the fail problems that arise from factors that they can control in their own daily businesses. These controls include the fail confirmation process, under which fails are confirmed with counterparties on a daily basis to ensure that all parties are on the same page. There is, then, a tremendous amount of pressure on the sales desk and operations to ensure that all settlement delivery instructions are updated on a regular basis to prevent delivery problems that might result in fails.

Trade confirmation and matching utilities are a key component of making sure that the latest information is readily available to market participants to ensure the timely flow of securities once they get to the settlement phase.

The mitigation of fail risk is crucial to the survival of the industry and its credibility. It is this knowledge that spurs it on to find new ways to deal with fails and, hopefully, to achieve an environment within which there are no fails. As difficult as that might sound, it remains a goal worth pursuing - but until that time comes, fails will continue to be as certain as death and taxes'.

NOTE

This paper reflects the views and opinions of the individual authors and not neccessarily those of their employers or other organisations with which they are associated.

REFERENCES

(1) The FICC is made up of the Government Securities Division (GSD), formerly known as the Government Securities Clearing Corporation (GSCC), and the Mortgage-Backed Securities Division (MBSD), formerly known as the Mortgage-Backed Securities Clearing Corporation (MBSCC). Both entities now fall under the DTCC umbrella.

(2) The TBA trade is much like a futures trade: settlement dates can be scheduled days, weeks, even months in the The seller is required to announce pools that will be delivered to satisfy trade at least 48 hours in advance settlement date. Failure to do so result in delivery being pushed out another 24 hours. For the purposes calculating net proceeds, however, settlement date never changes.